History of Science and Technology in Islam

TRANSFER OF ISLAMIC TECHNOLOGY TO THE WEST[1]

PART III

Technology Transfer in the Chemical Industries

Transmission of Practical Chemistry

Arabic works on alchemy and chemistry were translated into Latin in the twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. The first treatise on alchemy was translated by Robert of Chester in 1144. It was the dialogue between Khalid ibn Yazid and Maryanus the Hermit. Since then several alchemical works for Jabir ibn Hayyan (Geber), al-Razi (Rhazes), Khalid ibn Yazid (Calid), Ibn Umail (Senior Zadith) and others were translated also. Thus the Latin West became acquainted with Arabic chemistry and alchemy. This included the transmutation theories as well as the practical chemistry which involved the various chemical processes such as distillation, calcinations, assation, and a multitude of others. It involved also the laboratory equipment that was used to carry out the chemical processes such as the cucurbit, the alembic, the aludel, and the equipment needed for melting metals such as furnaces and crucibles. Knowledge of the various materials was included also such as the seven metals; the spirits of mercury, Sal ammoniac, and sulphur; the stones; the vitriols; the boraxes and the salts. Potassium nitrate was among the boraxes.

Nitric and Mineral Acids

During their extensive experimentation Islamic alchemists prepared mineral acids which they called sharp waters, among other names. They distilled the materials that produced nitric, sulphuric and hydrochloric acids.

It was established that the Arabic natrun and the Latin nitrum denoted frequently potassium nitrate in Arabic and Latin alchemy and that there are Arabic texts using natrun in the preparation of nitric acid and aqua regia which date from before the thirteenth century.

One of these recipes describes the solution of sulphur with acids, and is given in kitab al-mumarasa (the book of practice) that forms book sixty-five of the Book of Seventy by Jabir ibn Hayyan (d. about 815). The ingredients in the recipe are: rice vinegar, yellow arsenic (zarnikh asfar), natrun, alkali salt, live nura (unslaked lime), eggshells, and purified Sal ammoniac. Distillation produces aqua regia that is strong enough to put the sulphur into solution There is in Sunduq al-Hikma manuscript a recipe attributed to al-Razi which reads as follows: "Take the water of eggs, [of] one hundred eggs, and one quarter of one ratl from Sal ammoniac (nushadir), and two natrun, and Yamani alum (shabb) two qaflas. Bury this [mixture] in dung for seven days then take it out and distil it twice using the qar’ (cucurbit) and ambiq. This distilled water is suitable for zarnikh, sulphur and mercury".

In an Arabic treatise, Ta’widh al-Hakim we read a description of the preparation of aqua regia which is called al-ma' al-ilahi (the divine water) or ma' al-hayat (the water of life). The ingredients are natrun, alum, the viriol of Cyprus, and Sal ammoniac.

In the Liber Luminis luminum, that is attributed to al-Razi [2] we find a recipe for the preparation of nitric acid or aqua regia, that involves distilling a mixture of sal nitrum, Sal ammoniac and vitriol.

We find a recipe for nitric acid also in De inventione Veritatis which is a work in Latin ascribed to Jabir (Geber) that appeared at the end of the thirteenth century. Berthelot (end of nineteenth century) thought that this recipe for the preparation of nitric acid was the first of its kind. He went further to assume that Geber was not Jabir. This hypothesis of Berthelot is now baseless since there are in fact several Arabic recipes for nitric acid preceding the thirteenth century as we have just mentioned.

Explosive Gunpowder and the First Cannon

The first use of explosive gunpowder and cannon is another critical issue in the history of civilization. Gunpowder was first known in China but the mixture used was weak and not explosive. The proportions of the ingredients were not the right ones for cannon and the purity of the nitrate was not adequate because of the lack of a purification process.

In the thirteenth century the military engineer Hasan al-Rammah (d 1295 AD) described in his book al-furusiyya wa al-manasib al-harbiyya (The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices) the first process for the purification of potassium nitrate.

The process involves the lixiviation of the earths containing the nitrate in water, adding wood ashes and crystallization. Wood ashes are potassium carbonates which act on calcium nitrate which usually accompany potassium nitrate to produce potassium nitrate and calcium carbonate. The carbonates are not soluble and are precipitated.

Al-Rammah deals extensively in his book with explosive gunpowder and its uses. The estimated date of writing this book is between 1270 and 1280. The front page states that the book was written as "instructions by the eminent master Najm al-Din Hasan Al-Rammah, as handed down to him by his father and his forefathers the masters in this art and by those contemporary elders and masters who befriended them, may God be pleased with them all". It is unmistakable from this statement that Al-Rammah compiled inherited knowledge. The large number of gunpowder recipes and the extensive types of weaponry using gunpowder indicate that this information cannot be the invention of a single person, and this supports the statement of the front piece in his book. If we go back only to his grandfather's generation, as the first of his forefathers, then we end up at the end of the twelfth century or the beginning of the thirteenth as the date when explosive gunpowder became prevalent in Syria and Egypt.

The book contains 107 recipes for gunpowder. There are 22 recipes for rockets (tayyarat, sing, tayyar). Among the remaining compositions some are for military uses and some are for fireworks. The gunpowder composition of seventeen rockets was analyzed, and it was found that the median value for potassium nitrates is 75 percent.

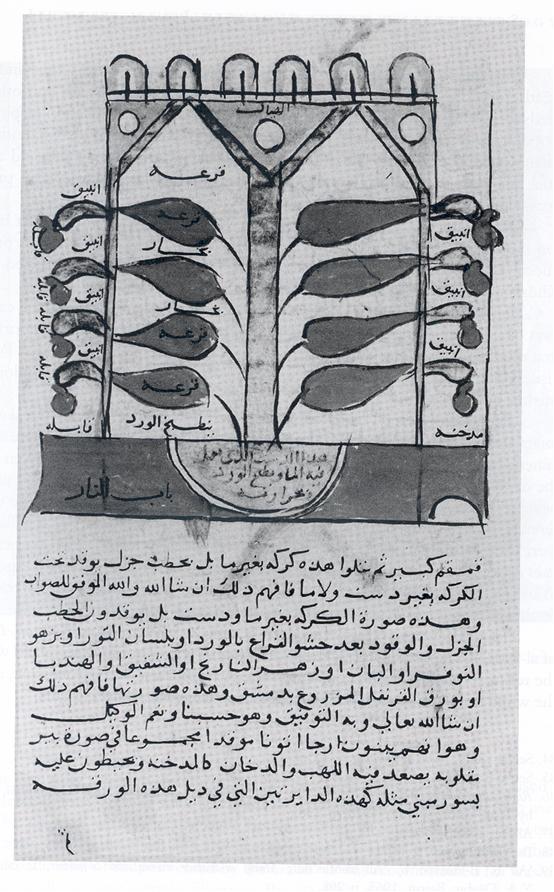

Two illustrations from an Arabic military treatise (known as the Petersburg manuscript) showing the first use of explosive gunpowder and cannon.

The ideal composition for explosive gunpowder as reported by modern historians of gunpowder is 75 percent potassium nitrate, 10 percent sulphur, and 15 percent carbon. Al-Rammah's median composition is 75 nitrates, 9.06 sulphur and 15.94 carbon which is almost identical with the reported ideal recipe.

Analysis of the composition of explosive gunpowder in several other Arabic military treatises of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries gave results similar to those of al-Rammah. These included the composition of gunpowder in the first cannon in history that was used, according to the military treatises, to frighten the Tatar armies in the battle of ‘Ayn Jalut in 1260.

The correct formula for the explosive mixture was not known in China or Europe until much later.

The Arabs in al-Andalus used cannon in their conflicts with the crusading armies in Spain and their first knowledge of the art was effective in their encounters. But ultimately the Muslim technology of gunpowder and cannon was transferred to Christian Spain and was used by them it the last encounters with the Muslims. From Christian Spain this technology reached Western Europe. We have mentioned in Part I of this article how the Earls of Derby and Salisbury, who participated in the siege of al-Jazira (1342-1344), took back with them the secrets of gunpowder and cannon to England.

Alcohol

The date of the first appearance of alcohol is another critical issue in the history of science. The distillation of wine and the properties of alcohol were known to Islamic chemists from the eighth century. The prohibition of wine in Islam did not mean that wine was not produced or consumed or that Arab alchemists did not subject it to their distillation processes. Some historians of chemistry and technology assumed that Arab chemists did not know the distillation of wine because these historians were not aware of the existence of Arabic texts to this effect.

The first reference to the flammable vapours at the mouths of bottles containing boiling wine and salt occurred in Kitab ikhraj mafi al-quwwa ila al-fi`l of Jabir ibn Hayyan (dc. 200/815).

This flammable property of alcohol was utilized extensively after Jabir and we find various descriptions of the alcohol-wine bottles in Arabic books of secrets and military treatises.

Literary evidence from Arabic poetry and prose indicate that distilled wine was consumed in the Abbasid period in the eighth century.

Among the early chemists who mentioned the distillation of wine is al-Kindi (d. 873) in Kitab al-Taraffuq fi al-'itr (also known as The Book of the Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations). Al-Farabi (d c.950) mentioned the addition of sulphur in the distillation of wine. Similarly Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi (d.1013) mentioned the distillation of wine when he was describing the distillation of vinegar from white grapes. Ibn Badis (d.1061) described how silver filings were pulverized in the presence of distilled wine to provide a means of writing with silver.

We find in the military treatises of the thirteenth and fourteenth century that alcohol from the distillation of old grape-wine became an ingredient in military fires.

In the fourteenth century alcohols were exported from the Arab lands of the Mediterranean to Europe. Pegolotti mentions alcohol and rose water among the list of exported commodities (1310-1340).

By the fourteenth century knowledge of the distillation of wine was transferred to the East and West and the word ‘araq in its various forms became widely used outside the Islamic lands of the Near East. The word arak was used for example by the Mongols in the fourteenth century. Mongol araki is first mentioned in a Chinese text in 1330. The word spread to most lands of Asia and the eastern Mediterranean.

It is assumed in Western literature that the earliest references in a Latin treatise to the distillation of wine occurred either in a text from Salerno around 1100 AD or in a cryptogram which was added by Adelard of Bath to the Mappae Clavicula (c. 1130). But the information given above indicates that knowledge about the distillation of wine preceded these dates and that both the recipe of Salerno and of Adelard of Bath were based on Arabic sources.

Most histories of distilled spirits inform us that the art of distillation of spirits is credited to the Arabs especially the Arabs of al-Andalus. Wine was distilled in al-Andalus as we have seen above (see al-Zahrawi), and sherry [3] was produced in Jerez. The word sherry comes from Sharish the Arabic name for Jerez.[4] The first to produce this were the Moors during their rule in southern Spain. We learn also from these histories that Armagnac was produced in the south of France some time before Cognac, and that it was probably produced by the Moors in the 12th century.

Perfumes and Rosewater

According to some historians of perfumes, the Arabs became for several centuries the perfumers of the world.[5] It is reported that among the many presents of Harun al-Rashid to Charlemagne were several types of perfumes. Forbes, the historian of technology, says that only with the coming of the golden age of Arab culture was a technique developed for the distillation of essential oils. By distilling their favourite flower, the rose, the Arabs succeeded in extracting from it a perfume that is still a favourite all over the world - rose water. Rose water came to Europe at the time of the Crusades.

Damascus was famous for its rose-water. We have detailed descriptions in the literature of rose-water distillation installations in Damascus. It was exported to several countries including Europe.

According to Arab geographers, rose water was distilled also in Jur, and in other towns in Fars. The rosewater of Jur was the best quality and it was exported to all countries of the world including: the Rum (Byzantium), Rumia (Rome) and the lands of Firanja (France and Western Europe), India and China.

A distillation plant in Damascus consisting of multiple units for producing rose water (13th century ms)

Soap

In Mesopotamia several detergents were known and used but soap as such was unknown. The classical world did not have better detergents, and bran, pumice-stone, natron, vegetable alkali and the like were used. Later on, Pliny described a soft kind of soap made by the Gauls but historians think that this was pomade made from un-saponified fat and alkali.

In medieval times the soaps that were made in northern Europe by the action of wood-ash lyes on animal fats and fish-oils were soft soaps of unpleasant odour. Personal cleansing by using hard soap was not a common practice in Europe.

Syria was renowned for its hard soap, which was pleasant to use for toilet purposes. Geographers of the tenth century reported that Nabulus in Palestine was prominent in its soap exports Soap was manufactured in the other Mediterranean Arab-Islamic lands including Muslim Spain where olive oil was abundant. In 1200 AD Fez alone had in it 27 soap manufacturers. In the thirteenth century, varieties of hard soap were imported by Europe from the Arab lands of the Mediterranean and were shipped across the Alps to northern Europe via Italy. The technology of soap-making was transferred to Italy and south France during the Renaissance.

Paper

The introduction and spread of the paper- making industry in the Near East and western Muslim Mediterranean, and then Europe was one of the main technological achievements of Islamic civilization. It was a milestone in the history of mankind. The manufacture of paper facilitated the production of books

Paper page, bearing an Arabic official document, writing on both sides

date: Fatimid Period (11th century AD)

at University College London

Remains of a Fabriano paper mill. Papermaking in Europe started in Fabriano, Italy.

on an unprecedented scale. Its diffusion and its replacement of parchment led to the evolution and success of printing, and with these two important achievements a true cultural revolution took place in human civilization.

Paper-making from mulberry bark started in China and it was a state monopoly. Chinese prisoners of war at the battle of Talas River in 751 started this industry in Samarqand. Before the end of the century there were floating paper mills on the Tigris River, in Baghdad. Paper mills then spread to Syria, to Egypt, and then to North Africa. Finally the manufacture of paper reached Muslim Sicily and Spain. Jativa became famous for its paper mills. Paper-making technology was then transferred to Italy and then the rest of Europe. The first paper mill in Europe was established in Fabriano in Italy in 1276, more than five centuries after the start of this industry in Samarqand and Baghdad. It took more than a century later before the first German mill was established in Nuremberg in 1390.

The Muslims revolutionized the industry of paper-making. They introduced several important innovations and the basic steps of Islamic paper-making technology remained virtually the same until modem times, the main later change being the conversion of the very small scale industry into a mammoth one by using huge modern machinery and modern methods of production.

Sugar

Sugar is a basic commodity that owes most of its development and spread to the Islamic civilization. It is thought that sugar-cane originated in eastern Asia from where it spread to India and then to Persia before Islam.

When Islam came to Persia in 642 AD sugar-cane was being grown and unrefined sugar was known. With the rise of the Arab-Muslim Empire sugar-cane spread into all the Islamic Mediterranean lands including Sicily and Spain and sugar production became a large scale industry.

Sugar refining was developed greatly and several qualities of sugar were produced and exported. Sugar became a foodstuff as well as a medicinal material in all Muslim countries and then in Europe.

Sugar was first known to western Europeans as a result of the Crusades in the 11th century AD. Crusaders returning home talked of this "new spice" and how pleasant it was. The first sugar was recorded in England in 1099. It became a luxury commodity in high demand. It is recorded, for instance, that sugar was available in London at "two shillings a pound" in 1319 AD. This equates to about US$100 per kilogram at today's prices.

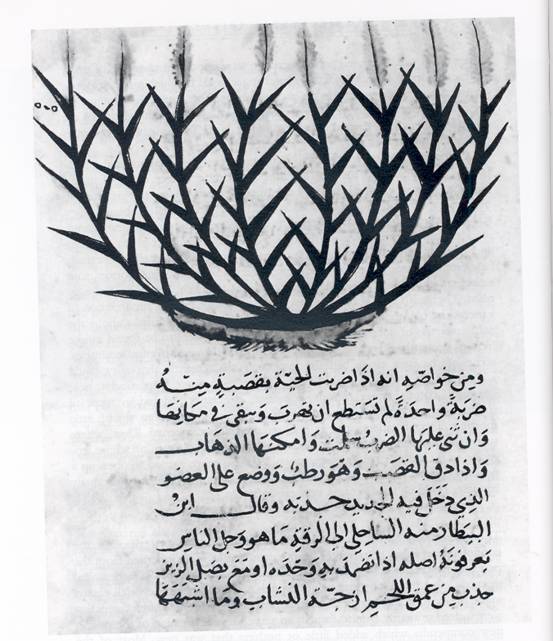

This illustration of sugar cane is from an Arabic manuscript on natural history.

Pegolotti in his lists of goods imported into Italy between 1310 and 1340 wrote that these included powdered sugar of Alexandria, Cairo, Kerak, Syria and Cyprus. Also lump sugar, basket sugar, rock candy, rose sugar, and violet sugar from Cairo and Damascus. England was importing its sugar from Morocco as well. We may remember that the words sugar and candy are both of Arabic origin.

From Spain sugar-cane plantations were established in the 1400's in Madeira, the Canary Islands, and St. Thomas. The Islamic technology of sugar-cane processing and sugar refining were established there.

In 1493 Columbus carried sugar cane cuts from the Canaries to Santa Domingo, and by the mid 1500's its manufacture had spread over the greater part of tropical America.

Glass

As was the case with the transfer of science to the West, the art and techniques of glass-working were transferred also. As mentioned in Part I of this article, the first phase of technology transfer took place in the eleventh century when Egyptian craftsmen founded two glass factories at Corinth in Greece. Here they introduced contemporary techniques of glass manufacture, but the factories were destroyed during the Norman conquest of Corinth in AD 1147 and the workers emigrated westwards to contribute to the revival of Western glass-making.[6]

Technology transfer took place again after the Mongol conquest of the thirteenth century AD, which drove large numbers of Syrian glass-workers from Damascus and Aleppo to glassmaking centres in the West.[7]

A third and a unique method of technology transfer, which reminds us of modern technology transfer, is a treaty which was drawn up in June 1277 AD between Bohemond VII, the titular prince of Antioch, and the Dodge of Venice. It was through this treaty that the secrets of Syrian glass-making were brought to Venice. Raw materials as well as Syrian Arab craftsmen were sent from Syria. The techniques of Islamic glass-making formed the foundations upon which Venice established its famous glass industry.[8]

Ceramics

The glazed and painted ceramics which are exhibited in world museums reveal the splendours of the glorious Islamic art of pottery. Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia and Persia had a continuous history in this art before Islam, but under Islam a revival took place, and the art spread throughout the Islamic World reaching Muslim Spain and then the West.

As early as the twelfth century the superior artistic pottery of Islamic countries had already attracted the notice of Europeans as an article of luxury for the wealthy. It is reported that Arab potters were brought into Italy, France and Burgundy to introduce the practice of their art, while Italian potters certainly penetrated into the workshops of Muslim Spain and elsewhere and gathered new ideas.[9]

Valencian tin-glazed wares, a legacy of the Andalusian wares, were exported to Italy, with Majorcan trading ships and were called maiolica (majolica). The Italian potters extended the name to the tin-glazed pottery which they made in imitation to the Valencian and the Andalusian wares. Another example is the Sgraffito ware. This technique was derived from the Islamic East through the Byzantine medium. It attained artistic importance in Italy towards the end of the fifteenth century and was made in Bologna until the seventeenth.

Tin glazing was an important development. Tin oxide was added to lead to render the glaze opaque. This tin glaze was decorated in cobalt blue, green and sometimes also manganese brown or yellow. This type was found in Samarra, was produced also in Persia and it reached Spain and then Italy. The golden pottery of Granada was tin-enamelled earthenware painted in metallic colours derived from silver and copper.

Tanning

The major tanning operations have come down from the earliest times as a slow empirical development. The Islamic civilization inherited the skills of the Near East and during several centuries tanning technology flourished and Muslim craftsmen contributed in developing this art. From Islamic craftsmen the know-how of leather-making began to reach Europe. A great variety of leathers were first introduced to the West by the Arabs in Spain. Morocco and Cordova leathers became widely known throughout Europe for their fine quality and pleasing colours. Through this technology transfer the tanning industry was already established in Europe in the fifteenth century. However the basic tanning technology remained unchanged, and until the end of the nineteenth century the only notable change in leather production was the introduction of power-driven machinery. The first change in 2000 years in tanning technology was the use of chrome salt at the end of the nineteenth century.

Other Transferred Technologies

The author of this article hoped to be able to include the transfer of other important technologies, but there is an inevitable length limit to any article. We did not discuss for example the textiles industries, nor did we speak about dyes and inks. We did not include the metallurgy of metals especially that of iron and steel. There is, as well, much information to include about building methods and the influence of Islamic architecture including the Mudejar one. Military technology, navigation, and artisan crafts deserve attention. It is hoped however that this article will be considered as a starting point for more exhaustive and detailed surveys in future.

[1] This Part II is taken from a revised version of the article published in Cultural Contacta in Building a Universal Civilization: Islamic Contributions, E. Ihsanoglu (editor), IRCICA< Istanbul, 2005, pp 183-223.

[2] Sometimes attributed to Michael Scot

[3] Sherry is a fortified wine. All sherry is fortified after fermentation with high-proof brandy, to about 16-18 percent alcohol, depending upon type, brandy used to fortify sherry contains about 80-95 percent alcohol by volume.

[4] César Saldana, General Manager of the Regulatory Council for Sherry, November 2002, http://www.crushmarketing.ca/Images Sherry/Sherry Seminar book 2072dpi.pdf

[5] Trueman, John, The Romantic Story of Scent (N.Y.: Doubleday, 1975), 83-84, 83.

[6] Singer et al., 328.

[7] Douglas, R. W. and S. Frank, A History of Glassmaking (Oxfordshire: G. T. Foulis & Co., Henley-on-Thames, 1972), 6.

[8] Sarton, G., Introduction to the History of Science (Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins), Vol. II, pt. II, 1040; see also Atiya, A. S., Crusade Commerce & Culture, (Indiana University Press, 1962), 238-239

[9] See T. Glick, Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1979), especially 238-241.

Copyright Information

All Articles and Brief Notes are written by Ahmad Y. al-Hassan unless where indicated otherwise.

The design of this website does not belong to Ahmad Y. al-Hassan, the design was based on common webdesign elements.

All published material are the copyright of the author (unless stated otherwise) and may not be published or reproduced in part or in whole without the express written permission of the author.